What can Big Chalk achieve? Using maps to understand its potential

The COP16 Conference is ongoing in Cali, Colombia with a focus on how the 196 countries which pledged to protect at least 30% of the world's land and water and restore 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030 will fulfill the commitment they made in 2022. It's a challenging goal: wildlife populations have shrunk by more than 70% over the last 50 years.

Collaboration is essential in realising these amibitions, but efforts must also be carefully planned and targeted or we run the risk of hitting the target while missing the point. Ecosystems function as a whole, so a push to plant trees in the wrong place could do more harm than good.

13 National Landscapes, one National Park and eight National Trails as well as a further 120+ partners are working together to deliver Big Chalk - one of the biggest nature restoration programmes happening in the UK currently. The programme covers 19% of England's land area and is very much a cause for hope. We look at the impact Big Chalk could have, but warn that meeting the 30by30 target only forms part of the picture.

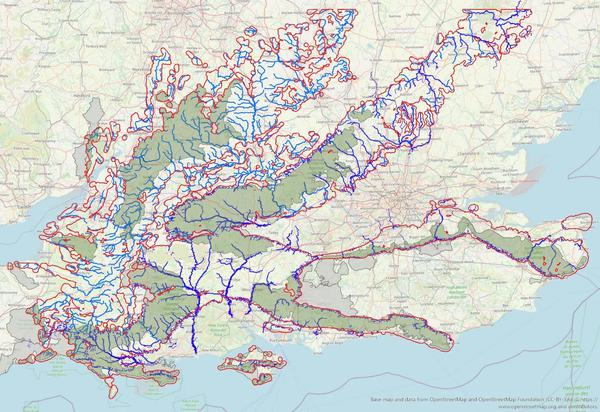

Big Chalk is a big idea - an area of 25,000km2 (19% of England) whose purpose is to link up nature recovery and related activities in the chalk and limestone areas of southern England. It spans 14 Protected Landscapes and 26 Local Nature Recovery Strategies, with more than 150 partners doing brilliant work on the ground. Big Chalk is still young and the inaugural conference in September was an opportunity to ask what Big Chalk can achieve. Big Chalk (the red outline), covers 19% of England and spans 14 Protected Landscapes (dark green), which make up a third of Big Chalk.

Big Chalk (the red outline), covers 19% of England and spans 14 Protected Landscapes (dark green), which make up a third of Big Chalk.

Against the background of declining nature across the UK, with species declining by, on average, 19% since 1970 and only 14% of protected sites in good ecological condition, we have an understanding of the wider tools available to roll out at scale across Big Chalk:

- The ‘Dimbleby Report’, suggests that halving food waste, increasing crop yields by 15% and eating 30% less meat could free up a third of the land for nature

- We can farm more sustainably and increase yields

- We know that physical and functional ecological networks are essential for wildlife to thrive

- Strengthening ecosystem services using nature is a cost-effective way to tackle environmental problems, with a bonus that it has the potential to bring in alternative sources of funding.

The ecology behind Big Chalk

Focussing in on Big Chalk, there are many places that either are already important for wildlife or have the potential to become important if they could all be brought under suitable management:

- Designated sites, such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), along with nature reserves cover 5% of Big Chalk. These have the highest levels of legal protection

- Woodland covers 10% of Big Chalk, not far off the average for England

- Priority habitat such as calcareous grassland and lowland hay meadows account for 15% of the area

- Big Chalk contains around 80% of the world’s chalk streams

If we could get all these managed well for nature, then that would be 16% of Big Chalk that would be wildlife friendly (there is overlap - for example, SSSIs are often also priority habitat). In reality, only about half of that area is actually managed for nature at the moment.

Water is an important part of Big Chalk. The area holds around 80% of the World’s chalk streams (dark blue) but only about 10% of the rivers and chalk streams are in good ecological condition.

Big Chalk’s contribution to national nature targets

The big one here is the internationally agreed target of 30% of land and sea protected and managed for nature by 2030 (30by30) that the UK has signed up to. If we meet that, then the rest of England’s national targets will either be met or well on the way to being met. Big Chalk shows the scale of that challenge. To hit 30% in the Big Chalk area would require 336,000ha of wildlife rich land to be created and around 200,000ha of the potentially good places brought into management - a very ambitious task but one that signatories to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, including the UK, agree is necessary.

The role of farming and food production (and Big Chalk’s partners)

This is a farmed landscape, with 71% being farmland (just over half of that is for crops), of which 14% is best quality land where the priority should be food production. 11% is farmland of the lowest quality, which is where there will be opportunities to move from economically challenging farming to managing the land primarily for nature. To do this farmers and land managers must be given the right support and incentives.

Indeed, if Big Chalk is to become an ecologically connected landscape, helping nature adapt to climate change and thrive across southern England, farmers and land managers have a vital role to play in helping develop and use the best farm management approaches to wildlife-friendly farming.

We know there are many farmers and land managers who care deeply about nature. This is reflected by dozens of farm clusters – collaborative groups of closely located farms – across Big Chalk who are prioritising wildlife in their management. With the right support from government and by drawing on the combined expertise and brilliant projects of our network of >150 partners, it’s possible to see how we can begin to work towards nature recovery across a whole region.

Big Chalk is a farmed landscape, with 14% being best quality land (blue). 11% is lowest quality land (brown).

So, in answer to the question “What can Big Chalk achieve?”, surely it must be to expand the amazing work already being done to the rest of the Big Chalk area, making a measurable difference for nature across 19% of England. This will create an ecologically connected, pan-regional nature recovery network, spanning political and organisational boundaries and allowing nature to adapt to climate change and thrive.

And we should be confident that it can work. The approach is based on strong evidence, the Lawton principles of bigger, better, more and joined up, the combined experience of committed partners and a rapidly growing understanding across the public, private and third sectors and general public that it’s time to help nature recover. But to do so, we need to think Big.

Prof. James Bullock, Ecologist, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology

and Bruce Winney, Nature Recovery Coordinator, National Landscape Association